Right Skill is the passport for migration

Right Skill is the passport for migration

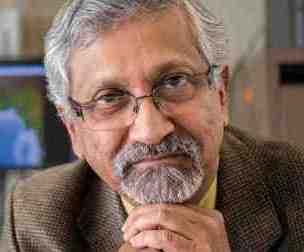

Prof Sekhar Bandyopadhyay, Head of School of History, Philosophy, Political Science and International Relations at the Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand, do not need an introduction. For scholars and academicians who have interest in India's caste system, Indian nationalist politics and Indian Diaspora, he is a known name. He has written, edited and co-edited several books on varied subjects. His books 'From Plassey to Partition and After, Caste, Protest and Identity in Colonial India and Caste, Culture and Hegemony: Social Dominance in Colonial Bengal, are particularly well-known and good reference points for scholars working in these areas. He was here in Delhi for the launch of his latest book 'Indians and the Antipodes: Networks, Boundaries and Circulation' which he edited along with Jane Buckingham. We spoke to him on the sideline of the event to understand the contemporary phenomenon and new direction that the human migration is taking in the new geopolitical order and the future of Diasporic lives in post-globalised era. An excerpt from the interview

Vijay K Soni: The book 'Indians and the Antipodes: Networks, Boundaries and Circulation' has touched upon various issues including some of the contemporary issues faced by the Indian Diaspora in New Zealand and Australia. Tell us more about the book.

It is a jointly edited book and it came out of a workshop that we organized on behalf of New Zealand India Research Institute. New Zealand India Research Institute has some well-defined themes and Diaspora happens to be one of them. We particularly have looked into the Indian Diaspora in New Zealand, Australia and also South Pacific. Two years back, the workshop invited scholars from New Zealand, Australia and Fiji and discussed the history of Indian Diaspora migration and how they came to South Pacific. Once the paper was presented, we found that a distinct theme has emerged and the theme was the interconnected nature of migration.

So, we realized that there was no reason why we should consider migration to New Zealand or Australia as separate phenomenon. They were all interconnected. The initial migration was for sugar plantation and the indentured labour system brought Indians to Fiji and New Caledonia, which was a French Pacific Colony. The people were brought under indentured system, which was initially for 5 years. Some people had second term as indentured for 10 years. But after 10 years they were free. So, by the time they became free they had collected some capital and started circulating in the region. Many of them migrated to New Zealand and some of them migrated to Australia and so on. There were also direct migration and Australia and New Zealand because of the demand of manual labour. In Australia sugar plantation was coming up in New South Wales and that’s how colonization started as forest had to be cleared and rail tracks had to be laid.

So, what were the profiles of the people who migrated initially and how did it changed over the course of generations?

There was demand for manual work in New Zealand and Australia and the Indians fulfilled the labour demands. Many of the early migrants were initially unskilled laborers. They worked and accumulated some initial capital. Once they had some capital they moved into some small enterprises like market gardening, small retail shops and so on. When they moved into entrepreneurial enterprises, they became an economy threat to local population. As long as they were doing manual work, they were not perceived as threat. But once they moved into enterprise, they were being looked upon as a kind of economic threat.

The other development that took place in the early 1900s was the First World War. When the war ended, Australian and New Zealand soldiers were coming back as the Army had been disbanded. The soldiers were looking for jobs and there was panic that the Chinese and Indians were depressing the labour market. The wage level was lower as Asians were doing the same work at a much cheaper rate than the local White population. That created what we might call the White backlash.

The White reaction was partly racial anxiety, partly economic insecurity and partly because of what they called it a civilization gap. It was a common perception that Asians were coming from inferior civilization, while New Zealand and Australia were experimenting with modern system of local self-governance, democracy etc. The argument during those times was that these people were not educated enough to participate in the democratic process. So, it was a kind of complex reaction. And that led to racial discrimination both in Zealand and Australia.

In 1901, Australia adopted strict White Australia policy. New Zealand followed the same. New Zealand changed the law in 1920, which restricted Asian migration. But there was a catch. The situation was better for the Indians because India was part of the British empire and as imperial subjects they had the rights to move anywhere in the British dominion as part of the Queen's Proclamation of 1858. London also intervened and said that Indians cannot be stopped from migrating. To beat that, British dominions come up with a novel tool and introduced language test, which was mainly English. So, those who failed the English language test could not get it.

But Indians are known for their innate maneuvering skills. How did they manage such an imbroglio?

Indians somehow learnt to circumvent the new regulation on their way to New Zealand. They used to stop at Fiji and there were kind of mugging schools. They used to memorize those forms and when they used to arrive at New Zealand port, they used to fill up those forms of language tests. To stop that, Australia came out with a novel solution that custom officer could recommend not just English language but any other European language. The immigrants were given translation in French, Portuguese or in Dutch. This was mainly to stop Indians. It was the White Australian policy. New Zealand was not that strict, it was more liberal and gave some rights to those who were already there and this went on till the Second World War. And after the Second World War, Australia finally abandoned the White Australia policy in 1970s and New Zealand in 1980s.

This was also the period of globalization when Australian and New Zealand economy was globalized. When you globalize, you have to open the labour market. It was the time when professional Indians migration started. There was massive Indian professional migration and this changed the composition of diaspora in New Zealand and Australia as were integrated with the global economy.

This book in a way, juxtapose to show that migration to these two countries were interconnected when it came to raising the racial barriers. But at the same time there were stories of resilience and enterprise. Indians were circumventing those barriers and establishing their networks in Fiji, New Caledonia, Australia and New Zealand. This kind of story is a rupture in the narrative of victimhood. Victimhood was certainly there, but these enterprising people also knew how to survive, how to take advantage and how to maneuver within the system.

The book has tried to juxtapose these stories of social mobility and inter-generational mobility. There is one chapter on Sir Anand Satyanand whose grandparents migrated as indentured laborers. His father went to New Zealand for medical education and became a doctor in Auckland and married another Fijian who was a nurse. Sir Anand Satyanand become a lawyer and then become a district judge and was subsequently appointed as Governor General. So, this was the trajectory from indentured laborer and in the course of few generations becoming a Governor General. These kinds of stories are also there. In other words on the one hand there is discrimination and victimization, while and on the other there are stories of struggle, resilience and social mobility and survival.

There are two stories side-by-side. The recent migration has changed the whole composition with more and more students and professionals coming to New Zealand and Australia. The earlier generation integrated into the mainstream society of the host countries more than the lot who came after 1990s.

The post-1990s migrants maintain a very close connection with their mother country. They have their opinion and get involved with the mother country more actively, which has never happened earlier. They also get connected with their mother country's politics. One needs to remember that India has diversity of opinion where one can support Left, Right or Central political parties. The Diaspora is also inclined on those ideological lines. It is not that the entire Diaspora supporters only one political party.

National politics in many developed countries have moved towards far right. How is it impacting migration?

Yes, this is a worldwide phenomenon including in the US and the UK and it is also happening in Australia and New Zealand. There is a rise of such groups including the Hindu groups who have united under the World Hindu Council. The young students and professionals are quite close to them. On the other hand, there is a sizable population of Diaspora who don't participate in such far-right activities. They believe in secularism and they maintain secular relationship with other communities. So, it's very divided and to think that all Non-resident Indians are on the Right is not right. The non-resident Diaspora is as pluralist as the home population. There are all the differences among them that we find in India - regional difference, linguistic difference, caste difference, and religious difference. In fact, in a way, all these things are kind of imported from the home country.

The book has a chapter as how caste operates among the Indian Diasporas. It is not that they go to a western society and they get egalitarian and they forget their caste. This brings in a lot of intra-community tension. The people of upper caste don't treat people from lower caste on equal footing. All kinds of inherited social biases work within the Diasporas as well. The only difference is that it has to be within the legal framework of the host country. For example, you cannot get away by lynching someone on the basis of someone's caste or religion. That's the major difference. No matter what social biases they bring in from the home country, they have to accept the rule of the law of the host country. There is less of, what I would call, hostile relationship. But the subtle differences still operate. In the community marriage they look for caste but lots of people marry outside their castes also. Lots of inter-community marriages are taking place that also create tension within the family and the community.

How has New Zealand and Australia proved as host countries for the Indian migrants?

Both in Australia and New Zealand, Indians constitute a very successful and significant community. They form four per cent of the population in New Zealand and 1.7 per cent in Australia. In terms of absolute number, Indians are more in Australia than in New Zealand. I would say New Zealand is more receptive to Indian migrants than Australia. It is more liberal in the sense that, while in Australia there are incidences of racism in terms of employment, such cases are negligible in New Zealand. There was a case of racial attack in Melbourne, these things never happen in New Zealand.

But in the whole, Indian community is well established in Australia and many Indians are on top position there. The Current Australian High commissioner to India, Harinder Sidhu, is a Punjabi. So, many Indians are doing fine in Australia and there is no overt racism. Both Australia and New Zealand have well-defined formula of migration on the basis of point criteria, qualification, age, and employability. If someone gets sufficient points on these bases, he/she gets the passage for migration. It is not based on race or country of origin.

Australia and New Zealand economy need skilled workers and Indians are known for being skilled. In comparison to Chinese, they can speak better English. It is one of the advantages. There are less number of cases of racism in Australia and New Zealand as compared to Europe. Europe is more racist than Australia and New Zealand, or even the US.

What are the most challenging issues faced by the Indian migrants in Australia and New Zealand?

Major challenges are the economic - you have to get a job. Job market is getting more and more tight and in order to get a job, you need to have the right kind of skills. Many students from India see education as immigration pass. They go there and do some degree. But those degrees do not get them a good job. New Zealand looks for required skills from their national interest perspective. For example, it does not make sense for New Zealand to get more restaurant managers from outside. New Zealand needs more computer technicians. They identify those skill shortages and recruit accordingly. In order to get a job in New Zealand, one has to fit into those skill shortage areas. One has to study where the gaps are and work out accordingly.

Do you think that developed countries have become less receptive to the idea of new immigrants joining their economy?

It hasn't happened in Australia and New Zealand. Globally, Europe and the US have seen these things happening. In the US there have been more such talks but no real steps have been taken up yet. The H-1B1 visa is still there. They have not stopped it yet.

The world is now moving towards more closed economy. This hasn't happened in Australia and New Zealand yet. Both Australia and New Zealand want to reduce migrants. In New Zealand for example, the net annual migration average was 70,000 and the current government wants to bring it down because it is putting lots of pressure on infrastructure. The real estate market in Auckland has gone beyond the roof. I mean just to rent a one-room in Auckland; you have to give 50 per cent of your salary. Now, it is the most expensive city in the world and more than 80 per cent of Indian population in New Zealand lives in Auckland.

The present Labour government is talking about reducing migration, which is not based on race. It is not saying that you stop Indian migration or Chinese migration. It is saying that we will identity skill shortage area and only those who have required skills in those areas will be given migration. So, from New Zealand national interest perspective there is a perfect legitimacy.

The earlier liberal policy believed in lifting the economy through migration. It was based on the assumption that you bring in more people and they will consume more and the economy will go up. But now it is being seen that it has other costs, particularly the pressure on infrastructure, housing, healthcare, school education, etc. Therefore, they want to bring down the net migration figure but not on the basis of race. The same thing is happening in Australia.

Do you think we are moving towards de-globalization?

There is a tendency towards that. But globalization has moved to such a level that reversing it will take time. It will not happen overnight. But there will be some tendency to go back. In recent years, nationalism has developed in various countries. You have more nationalistic and jingoistic kind of tendencies globally now.

How do you explain the growth of nationalism in recent years?

I think, it is a reaction to too much globalization. Globalization has not helped the lower rung of the society. It has created wealth only at the top. In some countries like India, it has created a large middle class but has not helped those at the bottom. Jingoistic nationalism is a force, which could divert people's attention from the real issues. Patriotism is a kind of emotion, which creates passion. This kind of populism is visible all over the world. I believe it is a kind of political game to distract the masses. That's the irony. The more globalization you have, the more regionalism, parochialism and nationalism it breeds.

Incidentally, the New Indian Diaspora in New Zealand and Australia has been actively participating in their homeland electoral politics through social media. How do you explain this phenomenon?

The older generation of migrants integrated more into the mainstream society of the host societies partly because the communication system, at that time, was not as efficient as it is now. Those who went to New Zealand and Australia could not come back to India easily and the only way to get in touch with people in India was through long distance call or through postal letters. There was very little communication between the home country and the host country for the migrants. People didn't know what was happening in India in those days.

Even now, when you took at the older migrants, they are culturally stuck in the period they left India. For example, those who left India in 1960s, their thoughts of India are in 1960s. They like those kind of songs, politics, people and so on. They are stuck in that time-space whereas the recent migrants are well connected with their home country. They chat with their relatives and friends every day.

We did a study on Indian students to find out whether they felt isolated in a foreign country, and what we found was that they were on either WhatsApp or Skype throughout the day and chatted with their friends and families back in India. So, when you communicate every day, you get involved in things and ideas of India.

The other thing is the question of identity. Because those involved in the politics of India also assert their identity in a foreign country where they do not always get that kind of recognition. If you are an Indian New Zealander or in Indian Australian, you are still not a full New Zealander or a full Australian, you are a kind of hyphenated. People would ask you where are you from? This creates a kind of mental problem that makes them conscious that they have another root. Better communication has given them an opportunity to get involved in homeland politics. So, there is a question of identity crisis as well.

Also, political parties like to cultivate this kind of relationship. This has happened partly by imitating the Chinese. It was the Chinese who started connecting with their Diaspora so that the Diaspora could contribute to the development of their economy. India learnt from them and started connecting with its Diaspora; Now Indian political parties actively cultivate this relationship, as a source of money and also as lobby groups. Indian Diaspora is now very much part of Indian politics. It's a two-way traffic. The Indian political parties need the Diaspora as much as and the Diaspora needs the homeland political parties.

What are the recent trends in the global migration and what are your concerns?

The latest trend is basically professionals and students migration. The major concern is that when students migrate they take lots of loans. There are compulsions to repay the loan and to do that you need to find a job overseas. The currency rate gives you the advantage. But as I mentioned earlier, you have to go for the right kind of skills to get the right kind of job. If there is a mismatch it won't happen. So in many cases students are very frustrated. The second risk is, as we are finding among the Indian students, not many of them are intellectually prepared. As a result, they fail the exam. We have had number of suicide case.

Some of the students had taken huge loans and they had failed. There were cases where these students couldn't cope up with the education system because it's very unlike in India. In India you could memorize and go and write your exam. In the West, the education system is quite original which expects its students to think and write their own answers. So, many of these Indian students can’t cope with that. These are the major risks.

It's not easy to go overseas and get education because all these institutes maintain a high standard. These universities have to compete globally and have to maintain its global ranking. So, in order to do that, we maintain high quality of education. Every one is not equipped to get into overseas higher education. There is also a bit of problem with these universities. They do not screen students before admitting them because they want fees. So sometimes, they ignore all these things. There were cases in which some of the institutions manipulated the documents; some of the agents in India also forged the documents.

When students arrive here, they have to face English language course, which is a norm in New Zealand. It was found that many of those scorecards were forged. The basic thing is that if you don't know English, you can't cope with the course and you can't pass. In those cases, their enrollments were cancelled and they were thrown out. There were number of such fraught cases.

Last year, some 230 students were deported from New Zealand because they had forged their documents. It is a very serious issue. The universities and institutions in New Zealand depend on agencies and it is very difficult for the government to regulate these agencies in India. These agents get their commission after a student is admitted into an institution. After admission, they are not concerned as to what happens to the students. They forge the documents and when these students land in a foreign country, they face the problem.

To study overseas is an investment. When someone invests into it, one has to carefully look into the risk. So, don’t forge the IELTS scorecard because it is not the scorecard, which is important. It is your English knowledge, which is important, and that knowledge is required to cope up with the pressure of education in these countries.

As an academician and a researcher, have you encountered any aspect of diasporic life that you would like to study given an opportunity?

I have number of projects in Diaspora studies but there is one in particular that I am keen to follow. In New Zealand, there is a very interesting case among the early Sikh migrants in the northern part of the country, in Hamilton area, to be specific. There are about 100 Sikh families, which practically operate and dominate the dairy market there. It is a very close-knit community, which organizes its life around the local gurudwara. They organize their marriages and maintain social connection through gurudwaras. Their history goes back to more than 100 years.

These Sikh families came to New Zealand as a farming community and in course of time set up their own businesses. Today, this close-knit community literally dominates the diary industry in the region. The gurudwaras have the system of langars. Many of these Indian students go there for free meal and these Sikh families pick up their future brides and grooms from them. That's how they have grown as a community over the years. Otherwise they would have been marrying within the community. They recruit people from the students who come here to study. It is a very interesting case and is a theme that's close to my heart and I would like to work upon in the future.

Interview Date: Tuesday, May 08, 2018

Person Name: Prof Sekhar Bandyopadhyay